How to read a scientific paper: a step-by-step guide

A scientific paper is a complex document. Scientific papers are divided into multiple sections and frequently contain jargon and long sentences that make reading difficult. The process of reading a scientific paper to obtain information can often feel overwhelming for an early career researcher.

But the good news is that you can acquire the skill of efficiently reading a scientific paper, and you can learn how to painlessly obtain the information you need.

In this guide, we show you how to read a scientific paper step-by-step. You will learn:

- The scientific paper format

- How to identify your reasons for reading a scientific paper

- How to skim a paper

- How to achieve a deep understanding of a paper.

Using these steps for reading a scientific paper will help you:

- Obtain information efficiently

- Retain knowledge more effectively

- Allocate sufficient time to your reading task.

The steps below are the result of research into how scientists read scientific papers and our own experiences as scientists.

Scientific paper format

Firstly, how is a scientific paper structured?

The main sections are Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. In the table below, we describe the purpose of each component of a scientific paper.

| Title | Description |

|---|---|

Title | Summarizes what the paper is about |

Author list | List of authors who contributed to the project. Order of authors depends on the conventions of the field. For example, in scientific fields like biological sciences, the first author wrote the first draft of the manuscript and is usually the corresponding author (the author who can be contacted with questions). In other fields like mathematics, the author list is in alphabetical order. |

Abstract | Concise summary of the paper. Usually 150-300 words. |

Keywords | Words or phrases that summarize the subject area of the paper. These terms facilitate searches in online databases or search engines like Google Scholar. |

Introduction | The first section of a paper where the questions or problem to be addressed is introduced. Background information on the problem, and a summary of how the questions will be addressed are included here. |

Methods | A description of the methods used in the research, which may include theoretical, empirical, and statistical analyses. There should be enough detail to reproduce the results. Some details may be found in the supplementary material as there might not be enough space for a full description in this section. |

Results | A description of what was found by the authors. Usually includes figures and tables. Some results not important for the overall take-home message may be found in the supplementary material. |

Discussion | Where the authors interpret their results, discuss the implications of their work, and integrate their work with findings from other authors. Some limitations of the study are outlined here. |

Conclusion | A statement that summarizes the overall findings and their implications. |

Appendix | Additional information, often theoretical or mathematical details. |

References | The list of journal articles, books, data, and other materials that were used to support the research project and the writing of the paper. Also called Literature Cited. |

Supplementary Materials | Additional supporting methods, results, and discussion that aren’t required to understand the overall message and content of the paper. May also include supplemental data. |

Because the structured format of a scientific paper makes it easy to find the information you need, a common technique for reading a scientific paper is to cherry-pick sections and jump around the paper.

In a YouTube video, Dr. Amina Yonis shows this nonlinear practice for reading a scientific paper. She justifies her technique by stating that “By reading research papers like this, you are enabling yourself to have a disciplined approach, and it prevents yourself from drowning in the details before you even get a bird’s-eye view”.

Selective reading is a skill that can help you read faster and engage with the material presented. In his article on active vs. passive reading of scientific papers, cell biologist Tung-Tien Sun defines active reading as "reading with questions in mind", searching for the answers, and focusing on the parts of the paper that answer your questions.

Therefore, reading a scientific paper from start to finish isn't always necessary to understand it. How you read the paper depends on what you need to learn. For example, oceanographer Ken Hughes suggests that you may read a scientific paper to gain awareness of a theory or field, or you may read to actively solve a problem in your research.

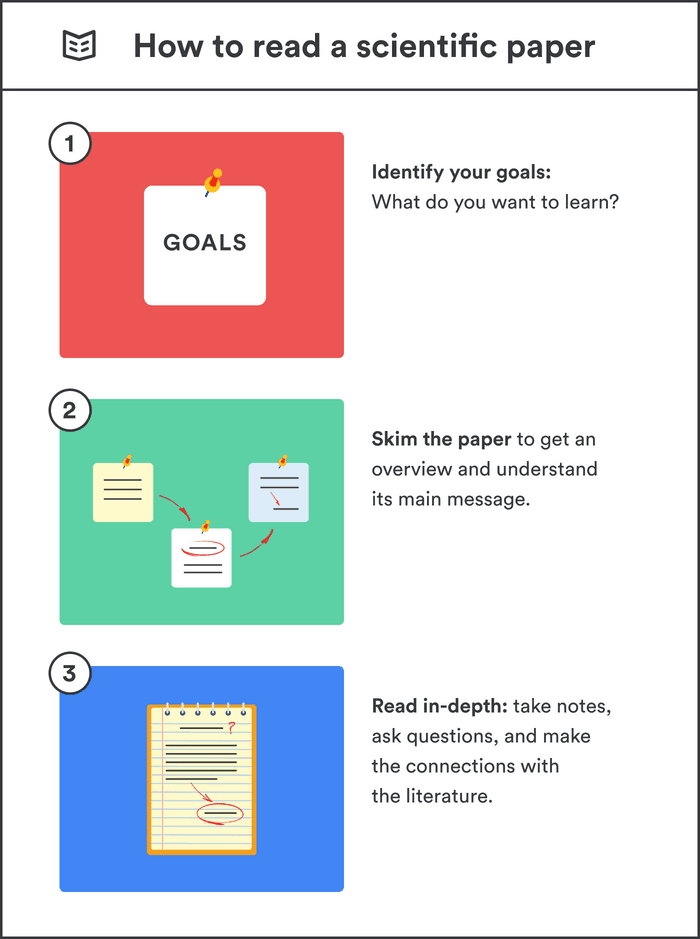

How to read a scientific paper in 3 steps

To successfully read a scientific paper, we advise using three strategies:

- Identify your motivations for reading a scientific paper

- Use selective reading to gain a high-level understanding of the scientific paper

- Read straight through to achieve a deep understanding of a scientific paper.

All 3 steps require you to think critically and have questions in mind.

Step 1: Identify your motivations for reading a scientific paper

Before you sit down to read a scientific paper, ask yourself these three questions:

- Why do I need to read this paper?

- What information am I looking for?

- Where in the paper am I most likely to find the information I need?

Is it background reading or a literature review for a research project you are currently working on? Are you getting into a new field of research? Do you wish to compare your results with the ones presented in the paper? Are you following an author’s work, and need to keep up-to-date on their current research? Are you keeping tabs on emerging methods in your field?

All of these intentions require a different reading approach.

For example, if you are getting into a new research field, to obtain background information and seminal references, you will be very interested in the introduction. You will also want to read the discussion, to understand the wider context in which the findings lie.

If you are following an author’s work, a cursory skim may be all that is required to understand how the paper lies within their overall research program.

If you are primarily interested in the study design and techniques the authors have used, then you will spend the most time reading and understanding the methods section of the paper.

Other times you need to read a paper that you may discuss in your own research, for example, to compare or contrast the work in it with yours, or to motivate a discussion point for future applications of your own work.

And if your aim is to extend the work presented in a paper, and consequently the study will form the starting point for your work, you will need to understand the paper deeply.

Knowing why you want to read the paper facilitates how you will read the paper. Depending on your needs, your approach may take the form of a surface-level reading or a deep reading.

Knowing your motivations will also guide your navigation through the paper because you have already identified which sections are most likely to contain the information you need. Approaching reading a paper in this way saves you time and makes the task less daunting.

Step 2: Use selective reading to gain a high-level understanding of the scientific paper

Begin by gaining an overview of the paper by following these simple steps:

- Read the title. What type of paper is it? Is it a journal article, a review, a methods paper, or a commentary?

- Read the abstract. The abstract is a summary of the study. What is the study about? What question was addressed? What methods were used? What did the authors find, and what are the key findings? What do the authors think are the implications of the work? Reading the abstract immediately tells you whether you should invest the time to read the paper fully.

- Look at the headings and subheadings, which describe the sections and subsections of the paper. The headings and subheadings outline the story of the paper.

- Skim the introduction. An introduction has a clear structure. The first paragraph is background information on the topic. If you are new to the field, you will read this closely, whereas an expert in that field will skim this section. The second component defines the gap in knowledge that the paper aims to address. What is unknown, and what research is needed? What problem needs to be solved? Here, you should find the questions that will be addressed by the study, and the goal of the research. The final paragraph summarizes how the authors address their research question, for example, what hypothesis will be tested, and what predictions the authors make. As you read, make a note of key references. By the end of the introduction, you should understand the goal of the research.

- Go to the results section, and study the figures and tables. These are the data—the meat of the study. Try to comprehend the data before reading the captions. After studying the data, read the captions. Do not expect to understand everything immediately. Remember, this is the result of many years of work. Make a note of what you do not understand. In your second reading, you will read more deeply.

- Skim the discussion. There are three components. The first part of the discussion summarizes what the authors have found, and what they think the implications of the work are. The second part discusses some (usually not all!) limitations of the study, and the final part is a concluding statement.

- Glance at the methods. Get a brief overview of the techniques used in the study. Depending on your reading goals, you may spend a lot of time on this section in subsequent readings, or a cursory reading may be sufficient.

- Summarize what the paper is about—its key take-home message—in a sentence or two. Ask yourself if you have got the information you need.

- List any terminology you may need to look up before reading the paper again.

- Scan the reference list. Make a note of papers you may need to read for background information before delving further into the paper.

Congratulations, you have completed the first reading! You now have gained a high-level perspective of the study, which will be enough for many research purposes.

Step 3: Read straight through to achieve a deep understanding of a scientific paper

Now that you have an overview of the work and you have identified what information you want to obtain, you are ready to understand the paper on a deeper level. Deep understanding is achieved in the second and subsequent readings. Here is a step-by-step guide.

- Read the paper from start to finish. This may be a slow process. As you read, take notes, and highlight important sentences. Note-taking and highlighting assist with:

- Active engagement with the material

- Critical thinking

- Creative thinking

- Synthesis of information

- Consolidation of information into memory.

Highlighting sentences helps you quickly scan the paper and be reminded of the key points, which is helpful when you return to the paper later.

Notes may include ideas, connections to other work, questions, comments, and references to follow up on. You can take notes in many ways:

- Print out the paper, and write your notes in the margins.

- Annotate the paper PDF from your desktop computer, or mobile device.

- Use personal knowledge management software, like Notion, Obsidian, or Evernote, for note-taking. Notes are easy to find in a structured database and can be linked to each other.

- Use reference management tools to take notes. Having your notes stored with the scientific papers you’ve read has the benefit of keeping all your ideas in one place. Some reference managers, like Paperpile, allow you to add notes to your papers, and highlight key sentences on PDFs.

Note-taking facilitates critical thinking and helps you evaluate the evidence that the authors present. Ask yourself questions like:

- What new contribution has the study made to the literature?

- How have the authors interpreted the results? (Remember, the authors have thought about their results more deeply than anybody else.)

- What do I think the results mean?

- Are the findings well-supported?

- What factors might have affected the results, and have the authors addressed them?

- Are there alternative explanations for the results?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

- What are the broader implications of the study?

- What should be done next?

Note-taking also encourages creative thinking. Ask yourself questions like:

- What new ideas have arisen from reading the paper?

- How does it connect with your work?

- What connections to other papers can you make?

- Write a summary of the paper in your own words. This is your attempt to integrate the new knowledge you have gained with what you already know from other sources and to consolidate that information into memory. You may find that you have to go back and re-read some sections to confirm some of the details.

- Discuss the paper with others. You may find that even at this stage, there are still aspects of the paper that you are striving to understand. It is now a good time to reach out to others—peers in your program, your advisor, or even on social media. In their 10 simple rules for reading a scientific paper, Maureen Carey and coauthors suggest that participating in journal clubs, where you meet with peers to discuss interesting or important scientific papers, is a great way to clarify your understanding.

- A scientific paper can be read over many days. According to research presented in the book "Make it Stick" by writer Peter Brown and psychology professors Henry Roediger and Mark McDaniel, "spaced practice" is more effective for retaining information than focusing on a single skill or subject until it is mastered. This involves breaking up learning into separate periods of training or studying. Applying this research to reading a scientific paper suggests that spacing out your reading by breaking the work into separate reading sessions can help you better commit the information in a paper to memory.

Final tips

A dense journal article may need many readings to be understood fully. It is useful to remember that many scientific papers result from years of hard work, and the expectation of achieving a thorough understanding in one sitting must be modified accordingly. But, the process of reading a scientific paper will get easier and faster with experience.

Other sources to help you read a scientific paper

Frequently Asked Questions about reading a scientific paper efficiently

❓ What is the best way to read a scientific paper?

The best way to read a scientific paper depends on your needs. Before reading the paper, identify your motivations for reading a scientific paper, and pinpoint the information you need. This will help you decide between skimming the paper and reading the paper more thoroughly.

❓ How do you read a scientific paper quickly?

Don’t read the paper from beginning to end. Instead, be aware of the scientific paper format. Take note of the information you need before starting to read the paper. Then skim the paper, jumping to the appropriate sections in the paper, to get the information you require.

❓ How long should it take me to read a scientific paper?

It varies. Skimming a scientific paper may take anywhere between 15 minutes to one hour. Reading a scientific paper to obtain a deep understanding may take anywhere between 1 and 6 hours. It is not uncommon to have to read a dense paper in chunks over numerous days.

❓ How do you read and understand a difficult scientific paper?

First, read the introduction to understand the main thesis and findings of the paper. Pay attention to the last paragraph of the introduction, where you can find a high-level summary of the methods and results. Next, skim the paper by jumping to the results and discussion. Then carefully read the paper from start to finish, taking notes as you read. You will need more than one reading to fully understand a dense research paper.

❓ How do you read a scientific paper critically?

To read a scientific paper critically, be an active reader. Take notes, highlight important sentences, and write down questions as you read. Study the data. Take care to evaluate the evidence presented in the paper.